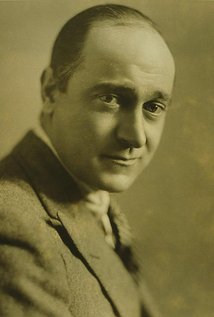

Born in London, Eric Blore came out of college and started his working life as an insurance agent. But while touring in Australia he took an interest in the stage and theater. He gave up his insurance job and turned to acting after returning to England. With his elfish long, straight nose, squint-eyed demeanor and a crisp voice, he successfully beg...

Show more »

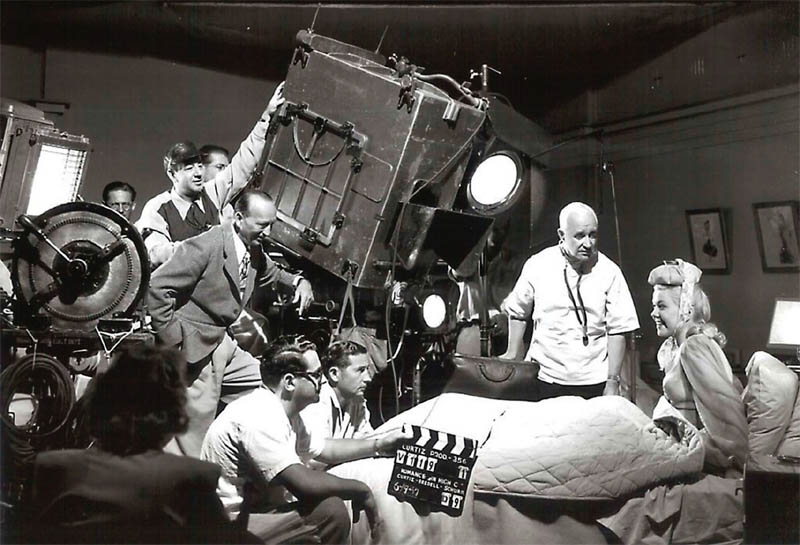

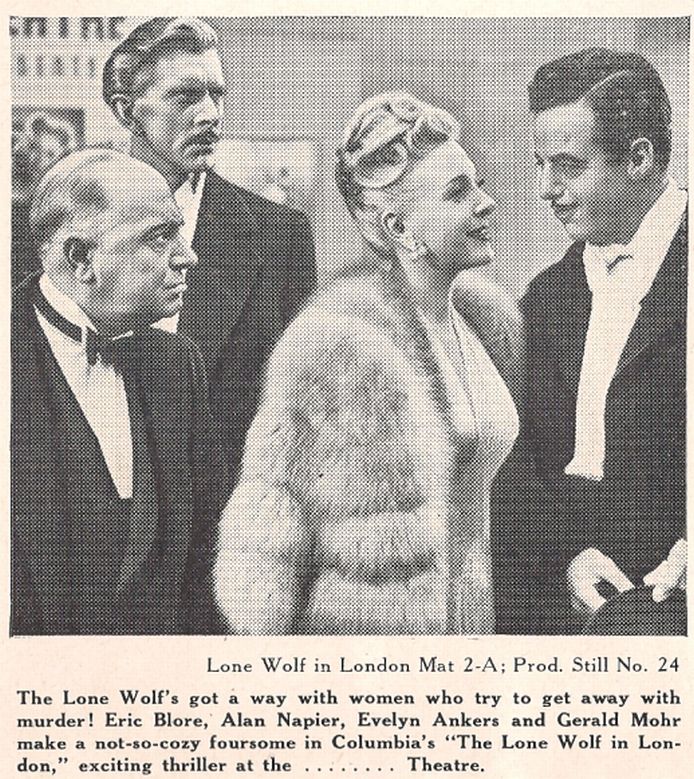

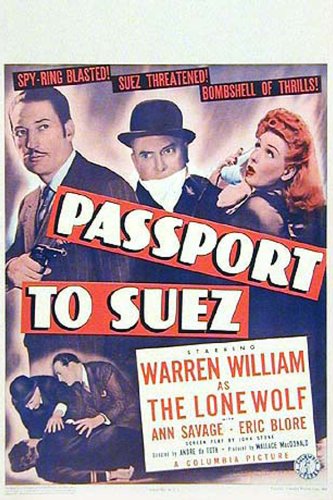

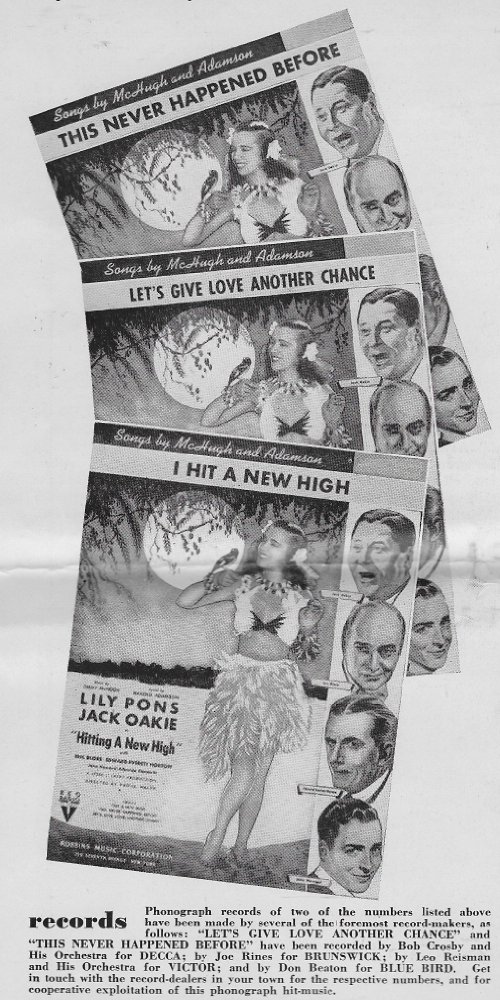

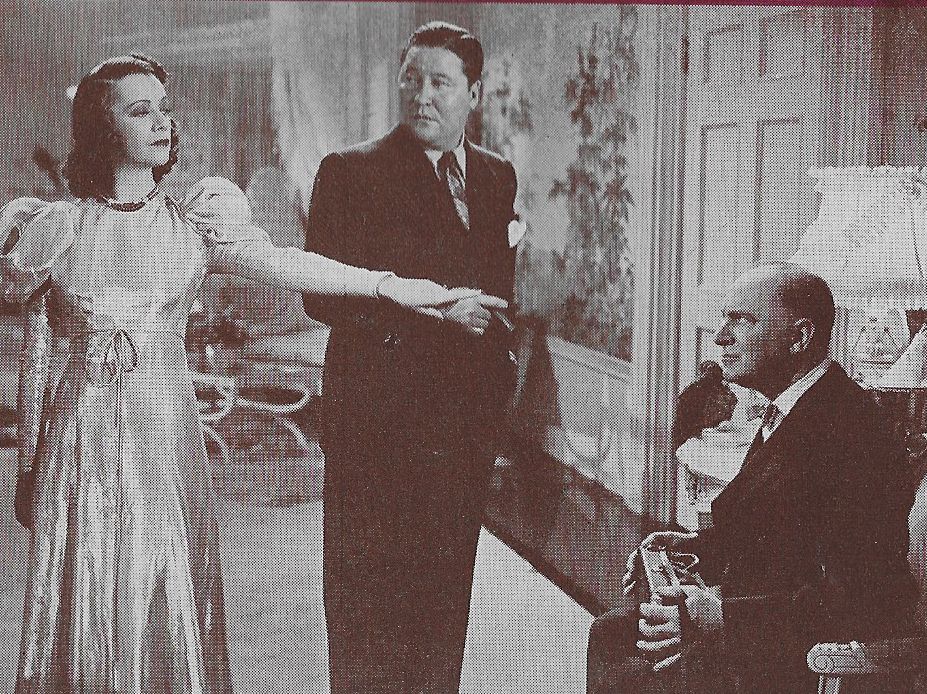

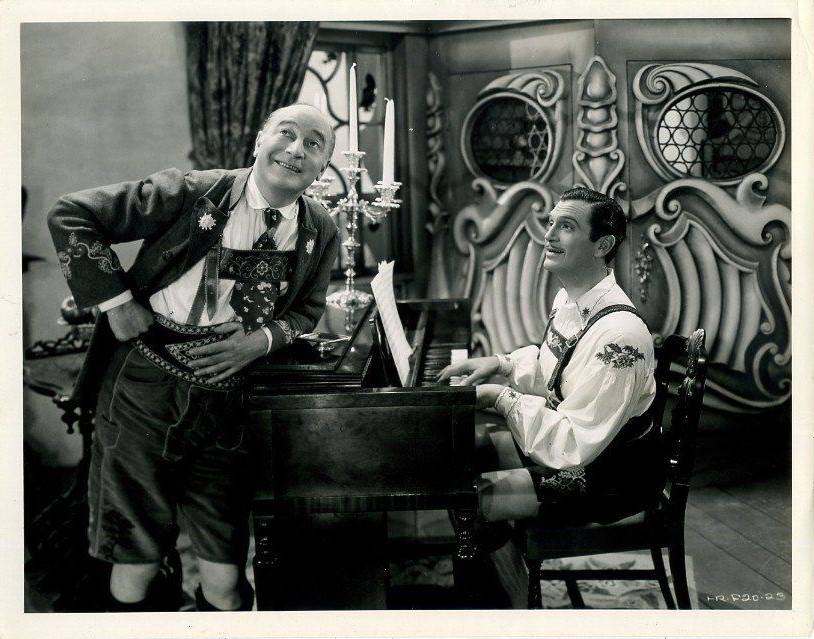

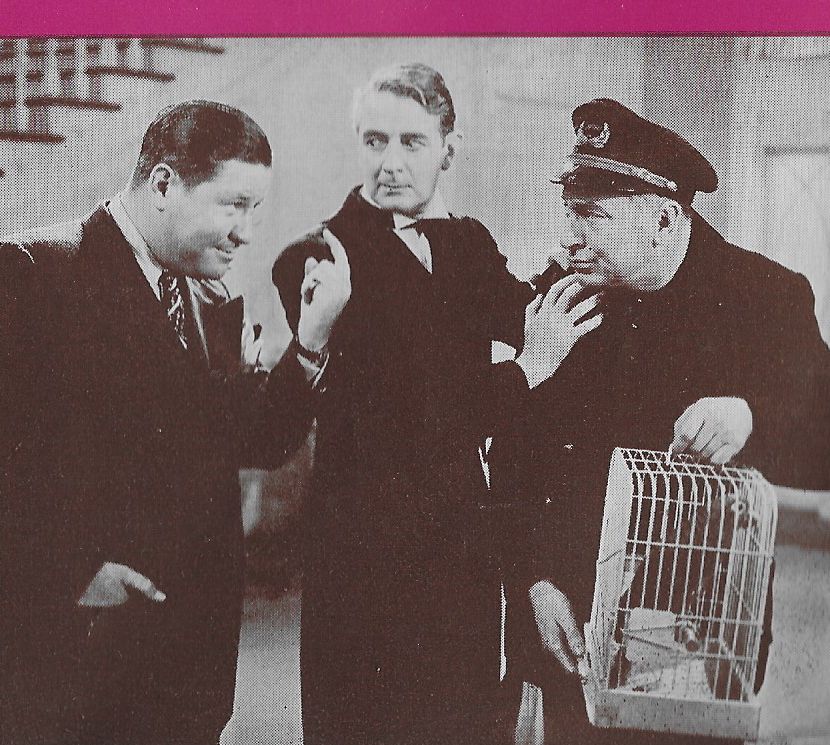

Born in London, Eric Blore came out of college and started his working life as an insurance agent. But while touring in Australia he took an interest in the stage and theater. He gave up his insurance job and turned to acting after returning to England. With his elfish long, straight nose, squint-eyed demeanor and a crisp voice, he successfully began a career starring in many shows and revues, focusing on traditional British comedy. Encouraged further, in 1923 he came to New York and was almost immediately using his London stage experience on Broadway. Though there were a few dramatic parts, he inevitably played comic roles in musical comedies and revues (in some of which he also received billing as a lyricist) regularly from 1923 to 1933. He would return once again some ten years later to take on multiple roles for Ziegfeld Follies of 1943. No stranger to film, as early as 1920 he had tried his hand in British cinema. And in 1926 he did the US silent version of The Great Gatsby (1926) that starred Warner Baxter. His familiar role as a head waiter began with his first Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers film, Flying Down to Rio (1933). With a foot still on Broadway, in 1933 he played the waiter in the stage version of The Gay Divorcee and was then tapped to reprise the role in the film version with Fred and Ginger. Blore had been perfecting his basic comic characters since his London days -- a leering English gentlemen, brusque/wise-acre butler or waiter or other service provider -- with a lockjawed British accent. These characters accompanied by Blore's flawlessly timed delivery were thoroughly applicable and effective as he moved permanently to Hollywood character acting. He played a fair spectrum of other roles, even in a few rare dramas, such as the adventure The Soldier and the Lady (1937) and Island of Lost Men (1939).Blore was very busy with movies from 1934 through most of the 1940s. He appeared in five of the nine Fred and Ginger dance musicals. Some of his best mugging and scripted lines were in Top Hat (1935) and Shall We Dance (1937) of that series. He was also cast very effectively as valet/butler Jamison in the screen adaptations of the Wolfe Kaufman Lone Wolf mystery novel series. There were eleven films between 1940 and 1947, with all but the last three starring the dashing, sonorous-voiced Warren William (who had a greater profile than 'The Great Profile', 'John Barrymore' ) as Michael Lanyard. This was a popular series with first-rate scripts and good production values to keep the public coming back for more. Blore was also invited into the company of stock players ruled over by zany comedy director Preston Sturges. Though Blore only did two films for Sturges, his role in the first of these, The Lady Eve (1941), was a Blore tour de force. Playing the suave confidence man, Pearly, to his old bunko acquaintances Barbara Stanwyck and Charles Coburn, he took the role of pseudo-wealthy Sir Alfred McGlennan Keith out to fleece the local American business gentry. His scene with a gullible Henry Fonda taking in Sir Alfred's concocted story of Stanwyck's being a twin daughter of the lady of the manor by way of her coachman is a delight, punctuated with Blore interrupting perplexed Fonda's questions with a loud shhhhhhh of silence at each.Inevitably, the parts started to become less frequent. Several of Blore's 1940s movies were with lesser known up-and-comers or older stars such as himself. Still, he enjoyed a variety of roles, including the opportunity of animation immortality when Disney chose him for the voice of Mr. Toad in the classic short The Wind in the Willows (1949). But for two widely spaced appearances, Blore essentially retired by 1955.And as sometimes is the case when personalities move into obscurity, their deaths are prematurely announced. Such was the case with Blore when the New Yorker journalist Kenneth Tynan reported him as having already passed on. Blore's lawyer raised a flurry, as did the editor of the New Yorker, who claimed the periodical had never had to print a retraction. The night before the highly profiled retraction appeared, Blore indeed passed away. And the next morning the New Yorker was the only publication with the wrong information. It seems likely Blore would have been particularly tickled with the irony of this last comedic bit in honor of his passing.

Show less «